A football helmet’s health warning sticker is pictured between a U.S. flag and the number 55, in memory of former student and NFL player Junior Seau, as the Oceanside Pirates high school football team prepared for a game in Oceanside, Calif., on Sept. 14, 2012. (Mike Blake/Reuters).

Omalu’s discovery has raised serious questions about whether there is any safe way for people to play football as the game is currently conceived. Those doubts about what is arguably the most popular sport in America reach all the way to the White House: President Obama has repeatedly said that if he had a son, he would not let the boy play football. Smith’s decision to play Omalu is a nod to that growing unease.

There is a particular vindication in the idea of Smith playing Omalu, given some of the struggles that Omalu, who is Nigerian and knew little about football when he began his research, has faced in his efforts to study players’ brains. Omalu’s work on CTE began when he performed the autopsy on former Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster. Omalu was struck by reports of changes in Webster’s personality toward the end of his life and wondered whether they might be due to head injury.

Last year, Omalu told Frontline reporter Michael Kirk that he had expected that the National Football League would embrace his findings. Instead, after Omalu submitted a paper to Neurosurgery, the journal where NFL doctors often submit their papers, the league sent a letter to Omalu’s colleague Cyril Wecht, accusing Omalu of fraud.

“They went to the press. They insinuated I was not practicing medicine; I was practicing voodoo,” Omalu said. Jabs at Omalu’s place of birth were routine, he told Frontline. “Some of them actually said that I’m attacking the American way of life. ‘How dare you, a foreigner like you from Nigeria? What is Nigeria known for, the eighth most corrupt country in the world? Who are you? Who do you think you are to come to tell us how to live our lives?’ ”That Omalu will not just get the big-screen biopic treatment, but gets to be played by Will Smith, one of the most successful black movie stars in the world and an icon of a certain kind of American success, is the sort of turnabout that feels exactly like fair play.

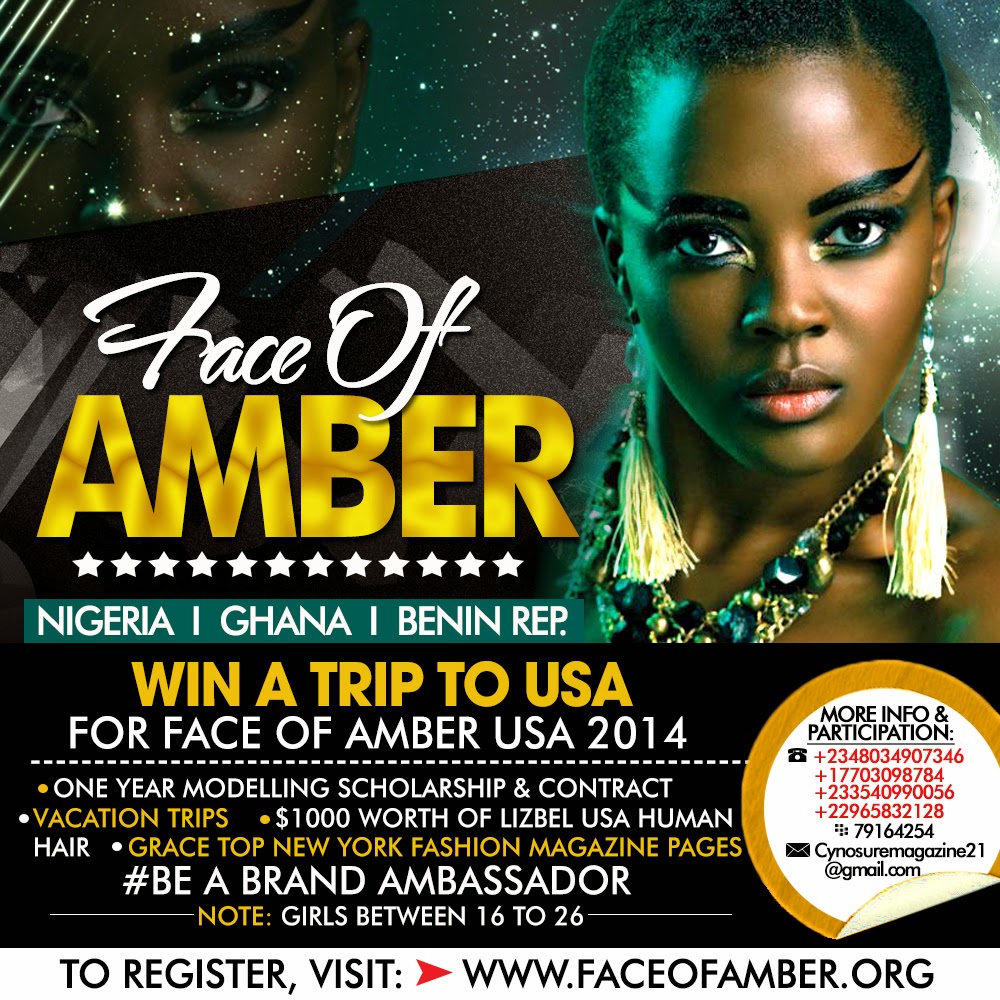

It is the cap on a shift in awareness that suggests the public — and NFL players — trust Omalu and his findings more than they trust the league. When veteran player Junior Seau committed suicide in 2012, he did so by shooting himself in the chest so that his brain could be studied after his death. His was the second such suicide by an NFL player in two years.

A 2013 Marist poll, conducted in conjunction with HBO’s Real Sports, found that 86 percent of Americans have heard at least something about the link between concussions and football. Thirty-three percent said that information would “make them less likely to allow a son to participate in the game,” with 16 percent saying that would be the most important factor in their choice. Thirteen percent reported that they would not let their sons play the game at all.

If those numbers increase, the NFL’s player pipeline could narrow, or even be shut off altogether, though it will be a long time until the NFL is in serious peril. Eighty-five percent of American families in the Marist poll would still let their boys put on pads. Thirty-five percent of Americans who follow sports name football as their favorite, with baseball lagging behind in second place.

In the interim, though, Smith’s movie will continue to advance the argument that it can be just as American to question the impact of football as it is to play the game. And if football players are American heroes, they deserve doctors with the same sense of determination and curiosity as Bennet Omalu looking out for them.

.jpg)